Three Dead Protocols

Previously on ugh blog dot jpg etc, I went on for 1000 words about dedicated ports. The tl;dr is that dedicated ports have got RFCs associated with them about what you, the savvy internet user, can expect to find should you connect to them.

I talked specifically about the internet’s favorite child, Port 80, but now it’s time to talk about three more: Ports 7, 13, and 17. They each have protocols with rules about what they’re to be used for, and that’s what this blog post is about. I have no idea if anyone is still using these protocols for, like, real reasons, or if they ever were, outside of testing, but I decided to implement them anyway, mostly just to see if I could. Turns out it’s really easy. We’ll start where I started on this adventure, with Port 17.

Quote of the Day

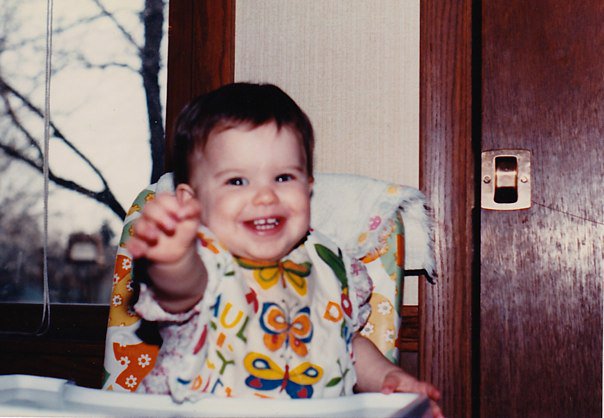

The internet’s beginnings were apparently a place of whimsy and, well, arbitrariness because Port 17, one of 1024 dedicated ports the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority has set aside for Official Use, is devoted exclusively to serving up a quote a day to anyone interested. You can read all about it in RFC 865, dated May 19831. In fact, all three of the protocols I’ll talk about today were published then. For reference, here’s what I was doing that spring:

I still have basically the same haircut. Anyways.

The protocol itself is really short – a scarce 216 words – but here’s an excerpt:

A server listens for TCP connections on TCP port 17. Once a

connection is established a short message is sent out the connection

(and any data received is thrown away). The service closes the

connection after sending the quote.

This was too good an opportunity to pass up, so I built my own. Conveniently, I’ve been clicking ‘like’ on pithy book and author quotes on Goodreads for years, and huzzah for me, they offer a CSV of my favorite quotes, which I downloaded and parsed for this purpose (aside: parsing text is so satisfying).

require 'socket'

require 'csv'

# a whole bunch of string parsing

# you can view on github if you're

# super curious

# fire up a server on port 17!

server = TCPServer.new 17

# format-a-quote

def qotd(quote, author)

"#{quote}\n - #{author}"

end

loop do

Thread.start(server.accept) do |client|

client.puts qotd(quote, author)

client.close

end

end(Github)

And that’s … it. It all feels rather anticlimactic, like there should be official forms to be filed with The Internet and weeks of waiting, but nope. If you’ve got a server, you too can open up Port 17 and shove some quotes inside.

Ways in which I am naughty and not compliant with RFC 865

At the risk of having my Internet license revoked, you should know my QOTD server isn’t entirely kosher:

- The protocol specifies quotes should be no more than 512 characters in length. I have some commented-out code in my github repo that takes care of this that in development worked fine but after some changes didn’t, and I was lazy and I haven’t gone back and fixed it. 512 seemed arbitrary, and it’s my server, so deal.

- When you connect to my QOTD server, you actually get a random quote from the list, not one per day. My reasoning for doing it this way is that the novelty is only there for about a minute, so you can up-arrow on your command line to your heart’s content and read random quotes from Dorothy Parker, David Foster Wallace, Simone de Beauvoir, and others for as long as interest persists.

- This isn’t about the protocol, but you should know my code for this is really sloppy because it was my first time attempting to use vim and literally everything was hard.

Please file all complaints via twitter.

Oh! And before I forget. I made this for you, internet friends:

nc pchs.co 17

Daytime Protocol

RFC 867, the Daytime Protocol, will tell you the day and time, for in case you’re not seeing it on your laptop or your phone, or your watch, or your tablet, or the clock, or the calendar, or you can’t ask the person sitting nearby you. Super handy.

This one’s fun because somebody was doing some copy/pasting from the QOTD protocol:

A server listens for TCP connections on TCP port 13. Once a

connection is established the current date and time is sent out the

connection as a ascii character string (and any data received is

thrown away). The service closes the connection after sending the

quote.

That last sentence look suspicious to you?

Here is the entirety of my code:

require 'socket'

server = TCPServer.new 13

loop do

Thread.start(server.accept) do |client|

client.puts Time.now

client.close

end

end(Github)

Should you need it, you can find out the date and time with this magical incantation:

nc pchs.co 13

Echo Protocol

Our last contestant, the shortest of three already-short protocols, comes to us via RFC 862, the Echo Protocol. Excerpt:

A server listens for TCP connections on TCP port 7. Once a

connection is established any data received is sent back. This

continues until the calling user terminates the connection.

Ah! Something a little different this time.

As before, here is the entirety of my code:

require 'socket'

server = TCPServer.new 7

loop do

Thread.start(server.accept) do |client|

while true

msg = client.gets

client.puts msg

end

end

end(Github)

For all its vacuousness, this one forced me to think ever-so-slightly more about what I needed the code to do. First, I needed to capture input from the user on the other end (msg = client.gets). Second, note that the protocol stipulates that the client closes the connection, not the server.

Now you can echo to your heart’s content via the command line:

nc pchs.co 7

(Just Ctrl + C when you’re done.)

Why even bother

I have a couple responses to this question-shaped declaration:

- For shits and giggles.

- I’m at Recurse Center. It’s kindof my job rn, you guys. I’m following my muse down a rabbit hole, etc.

Visiting these abandoned ports and implementing these three adorable protocols demystified a lot of the stuff about servers that confused me most, stuff like, “soooo a port does what exactly?” “Where do I get a server?” (Write it yourself!) “What do I do with it when I get there?” (Maybe there’s an RFC that will tell you!) “How does a server serve things?” (It’s in the code you wrote, dummy.) “How does a client talk to a server and how does the server hear it?” (Also in the code! It turns out COMPUTERS DO WHAT YOU TELL THEM TO DO.)

Having done this, it’s now time to move on to meatier things. In my previous post I mentioned I was reading RFC 2616, and welp, I’m not just doing it because I’m bored on the subway. This week I started writing my own HTTP server. It’s not much yet (turns out a 175-page protocol is more complicated than a half-page protocol), but if the client’s message starts with GET, the server responds with 200 OK and a little “hi this is ann” message body. Stay tuned!

-

Errata: The original footnote here stated that RFC 2616 was published in 1983. It was very definitely not. (How embarrassing.) RFC 2616 was publish in June 1999. Thanks to this HN comment for pointing it out! ↩